5· Inside Out

- Which dreamed it?

- The split and image

- Outsights and insights

- The astonishing hypothesis

- Umwelt and Innenwelt

- Mythic universe

- Faces and things

- Wholes in our logic

- Mediation and meditation

On her journey Through the Looking Glass, Alice encounters the Red King, lying asleep and snoring on the grass.

‘He's dreaming now,‘ said Tweedledee: ‘and what do you think he's dreaming about?’

Alice said ‘Nobody can guess that.’

‘Why, about YOU!’ Tweedledee exclaimed, clapping his hands triumphantly. ‘And if he left off dreaming about you, where do

you suppose you'd be?’

‘Where I am now, of course,’ said Alice.

‘Not you!’ Tweedledee retorted contemptuously. ‘You'd be nowhere. Why, you're only a sort of thing in his dream!’

‘If that there King was to wake,’ added Tweedledum, ‘you'd go out – bang! – just like a candle!’

‘I shouldn't!’ Alice exclaimed indignantly. ‘Besides, if I'm only a sort of thing in his dream, what are you, I should like to know?’

‘Ditto,’ said Tweedledum.

‘Ditto, ditto!’ cried Tweedledee.

He shouted this so loud that Alice couldn't help saying, ‘Hush! You'll be waking him, I'm afraid, if you make so much noise.’

‘Well, it no use your talking about waking him,’ said Tweedledum, ‘when you're only one of the things in his dream. You know very well you're not real.’

‘I am real!’ said Alice and began to cry.

‘You won't make yourself a bit realler by crying,’ Tweedledee remarked: ‘there's nothing to cry about.’

‘If I wasn't real,’ Alice said – half-laughing though her tears, it all seemed so ridiculous – ‘I shouldn't be able to cry.’

‘I hope you don't suppose those are real tears?’ Tweedledum interrupted in a tone of great contempt.

— Through the Looking Glass, Chapter IV

As it turns out, Alice with her Lacrimo, ergo sum and Tweedledum with his metaphysical interruption are both wrong: it's Alice who's dreaming the whole show – not Alice the character in this dialogue, but Alice who wakes up at the end of the story. But that Alice is herself a figment of Lewis Carroll's imagination. But then who is this “Lewis Carroll”? And when Alice Liddell (the original model for “Alice”) read this story, did she see herself through the looking glass, or a figment of Carroll's imagination, or of her own? When you read it yourself at this end of time, who does the King represent?

Who's the real dreamer now? Certainly not Alice or any character in dream or story – including ‘that there King’ – and certainly not you as the person you imagine yourself to be. No, it's you as the ground and Creator of all these characters, these apparitions. The one who speaks for that Creator is the primal person. Or as Dogen Zenji says,

The place where the dream is expressed within a dream is the land and the assembly of buddha ancestors. The buddhas’ lands and their assemblies, the ancestors’ way and their seats, are awakening throughout awakening, and express the dream within a dream. When you meet such speech and expressions, do not regard them as other than the buddhas’ assembly; it is buddha turning the dharma wheel.… This is the dream expressed within a dream, prior to all dreams.— SBGZ ‘Within a dream expressing the dream’ (Tanahashi 2010, 431)

For the primal person there can be no difference between self and other, or subject and object, or appearance and reality. The lived and living universe of experience is the universe, period. Primal person has a whole world, and this having is not separate from being, nor this being from becoming. (Could you also call it be-having?)

The trouble with talking about the primal is that its absolute immediacy eludes language, even precludes all semiosis. It is the First in Peirce's triad of ‘categories,’ which are the basic relational elements of whatever appears. Here is how he introduced the triad in his ‘Guess at the Riddle’ (c. 1888):

The First is that whose being is simply in itself, not referring to anything nor lying behind anything. The Second is that which is what it is by force of something to which it is second. The Third is that which is what it is owing to things between which it mediates and which it brings into relation to each other.

The idea of the absolutely First must be entirely separated from all conception of or reference to anything else; for what involves a second is itself a second to that second. The First must therefore be present and immediate, so as not to be second to a representation. It must be fresh and new, for if old it is second to its former state. It must be initiative, original, spontaneous, and free; otherwise it is second to a determining cause. It is also something vivid and conscious; so only it avoids being the object of some sensation. It precedes all synthesis and all differentiation: it has no unity and no parts. It cannot be articulately thought: assert it, and it has already lost its characteristic innocence; for assertion always implies a denial of something else. Stop to think of it, and it has flown!

What the world was to Adam on the day he opened his eyes to it, before he had drawn any distinctions, or had become conscious of his own existence,— that is first, present, immediate, fresh, new, initiative, original, spontaneous, free, vivid, conscious, and evanescent. Only, remember that every description of it must be false to it.

— Peirce (EP1:248, CP 1.356)

As Ta Hui put it, ‘the mindless world of spontaneity is inconceivable’ (Cleary 1977, 19). This would explain why those mystics who try to articulate the primal experience typically testify to the inadequacy of their own expression. To them, the discrepancy between the reality of the experience and the falsity of the description is unbearable. (“Reality of the experience” is a dumb expression too.)

Jesus said, ‘When you see your likeness, you are happy. But when you see your images that came into being before you and that neither die nor become visible, how much you will bear!’ — Gospel of Thomas 84 (Meyer; 5G marks the last part as a question.)

There's no use trying to describe an invisible image. Peirce might say it is a First without Secondness, meaning a possibility which has not yet come into existence. A Buddhist might say it is uncreated. None of these expressions can mean much to you unless you've had some inkling of the experience, but it is possible to outline a practice that could point you in that direction. I've tried to do this in a little chapter on phenoscopy, one of Peirce's names for such a practice. In this chapter, though, i'll settle for trying to explain why the world is inside out.

If the primal is Peirce's Firstness, separate existence – setting self against the other by force of which ‘it is what it is’ – is Secondness. What brings them together again is Thirdness, the element of mediation and representation. In his first exposition of ‘phenomenology,’ Peirce introduced this third category with a story from the Arabian Nights:

The merchant in the Arabian Nights threw away a datestone which struck the eye of a Jinnee. This was purely mechanical, and there was no genuine triplicity. The throwing and the striking were independent of one another. But had he aimed at the Jinnee's eye, there would have been more than merely throwing away the stone. There would have been genuine triplicity, the stone being not merely thrown, but thrown at the eye. Here, intention, the mind's action, would have come in. Intellectual triplicity, or Mediation, is my third category.CP 2.86 (1902)

The element of intention is involved in any act of meaning, including the attempt to lend a tongue to the primal, but also including utterances or interpretations that are not consciously intended. Mediation, the sign mediating between object and interpretant, is the only means of meaning. The ‘triplicity’ of object-sign-interpretant is irreducible to simpler relations, and thus just as “elementary” as the Primal or Secundal (Peirce, EP2:270). Firstness and Secondness are always involved in the Thirdness of Mediation, but neither could do any meaning by itself. Both are, strictly speaking, mindless.

If the primal person could take a philosophical stance, it would be the one called solipsism, which turns Tweedledum's opinion inside out: as a solipsist, rather than taking all of us to be figments of somebody else's dream, I take everybody else to be figments of mine. But since any philosophical stance presupposes a dialogue with other selves, as we saw in Chapter 2, a solipsistic stance would contradict itself in practice. The only practical common-sense belief, then, is some kind of realism: you have to believe that the other is really out there, and you're not making it all up. (Here the gulf opens up between you and the primal person.)

Reflect: if you were making it all up, there would be no difference between appearance and reality – between the world and your perception of it. But you know there's a difference because the world is full of surprises: your expectations often turn out to be wrong. Your knowledge is fallible: there's a difference between the reality out there and your perception of it: both you and the other exist in your Secondness to each other. Besides, you have every scientific reason for believing that your whole awareness of the external world is a performance of your brain. Yet it's a performance that you can't watch as taking place in your head. Only an outside observer can see your brain's performance, and that third person can only guess what it feels like to you.

As Maturana (1978a) pointed out, only an observer can distinguish between the “inside” and “outside” of an organism. It is only when you recognize “yourself” as one subject among many, and thus become a self-observer, that you have an “inner” life. Whether we should speak of this inner life as “observed” or “inferred” by others is not a simple question, but clearly they can observe (if suitably equipped) a sequence of brain states, a network of neural dynamics, which correlates so closely with your experience that it appears to constitute your inner life. But the nervous system, unlike your private experience itself, appears in the external world, the world observable by others as well as you. Careful observation of that world leaves little room for doubt that the nervous system itself does all the thinking and feeling, including observation. Realistically, then, you have to agree that the world is inside out. It appears ‘out there’ because of your own inner workings, which in turn appear to be ‘inner’ only from the outside.

It's as if you have twin “selves,” one to experience the world – the subject (who is also the king) of experience – and one to play a part in the world (and thus be subject to it). Let's call the former Dum and the latter Dee. Language being a social phenomenon, it's Dee who does all the talking. In trying to identify the other self, the subject who is king, Dee conjures up a ghostly twin of itself in the form of a disembodied person (“self,” “soul,” .....). Knowing that embodiment is temporary, some of us cling to the notion of a permanent self, a spiritual First Person who matters more than any mere bodymind. (Sometimes we forget that everything that matters matters to somebody.)

Confusing that unchanging ‘First Person’ with the uncreated ‘primal person’ can lead to ‘subjective and objective self-addictions’ (Thurman 1994, 46). The cure for these addictions is the realization that the first person is only one limited point of view, because there are others ‘who are every one sole heirs as well as you’ to the glories of heaven and earth. To achieve this exalted humility requires us to experience the inconceivable and to see the familiar as utterly strange: it requires a resurrection of the lived body as the living.

The body of man is a microcosm, the whole world in miniature, and the world in turn is a reflex of man.— Haggadah (Barnstone 1984, 25)

In ourselves the universe is revealed to itself as we are revealed in the universe.— Thomas Berry (1999, 32)

Yet all this which seems, in a way, so paradoxical and so difficult to grasp, is the simplest and most obvious thing in the world. It is neither more nor less than discovering, rediscovering, where one actually stands, the actual ground of one's experience. — Oliver

Sacks (1984, 182)

Be strong, and enter into your own body: for there your foothold is firm. Consider it well, O my heart! go not elsewhere.

Kabir says: ‘Put all imaginations away, and stand fast in that which you are.’ —

Kabir II.22 (Tagore 1915)

Jesus said, ‘I took my stand in the midst of the world, and in flesh I appeared to them.’ — Gospel of Thomas 28.1 (Meyer)

Why abandon the seat in your own home to wander in vain through the dusty regions of another land? If you make one false step, you miss what is right before you. Since you have already attained the functioning essence of a human body, do not pass your days in vain; when one takes care of the essential function of the way of the Buddha, who can carelessly enjoy the spark from a flint? Verily form and substance are like the dew on the grass, and the fortunes of life like the lightning flash: in an instant they are emptied, in a moment they are lost. — Dogen, Fukan zazen gi (Bielefeldt 1988, 186)

Once the primal One has fallen apart, splitting into self and other, the view from within the self-defined system is oriented outward (toward the other) by default. You simply can't navigate the world without seeing it as something really out there to be navigated. Questioning that default assumption would interrupt your navigation. This is not necessarily a bad move, since a temporary interruption might improve navigation in the long run; but you'd be sunk if you did it all the time.

Science, being the formal and public face of common sense, has to make that same default assumption in the course of its inquiry. Therefore when it looks into subjects like you and the way you see your world, it can only confirm the words of Blake, that ‘in your own Bosom you bear your Heaven and Earth & all you behold; tho' it appears Without, it is Within’ (Jerusalem 71:17). Current science may prefer ‘brain’ to the poet's ‘Bosom,’ but that's a matter of style that doesn't really matter.

The discovery that the world is inside out is not new. Indeed it was clearly stated close to 3000 years ago in the Upanishads:

Within the city of Brahman, which is the body, there is the heart, and within the heart there is a little house. This house has the shape of a lotus, and within it dwells that which is to be sought after, inquired about, and realized. … As large as the universe outside, even so large is the universe within the lotus of the heart. Within it are heaven and earth, the sun, the moon, the lightning, and all the stars. What is in the macrocosm is in this microcosm.

— Chandogya Upanishad (Prabhavananda and Manchester 1947, 119)

However, some discoveries continue to be surprising long after their truth is recognized, because they still appear to conflict with entrenched conceptual habits. We might call them macro-surprises, or revelations. They are startling at first, shaking up the cognitive scene just as revolutions shake up the political scene (or the scientific scene, according to Thomas Kuhn). But they also continue to seem paradoxical because they collide with our habitual way of seeing the world – which we habitually confuse with the world itself. We may therefore see revelations as coming from beyond the world or anyone in it. Many religious traditions would trace them to a “supernatural” source, since “nature” is identified with the world as we habitually know it. Yet our explorations of the natural world itself bring even bigger surprises.

In the human dialog with nature which we call science, nature talks back to us in unexpected ways. The current renewal of the revelation that the world is inside out follows upon a string of scientific revelations, many of which have revealed things we could have guessed but weren't prepared to believe.

We had known for centuries, even some of the ancient Greeks knew, that the earth was a sphere floating in space; but the knowledge never really came home to most of us earthlings until the first pictures of our planet were taken from far enough away to see it all at once. (It still amazes me that this took place within my own lifetime; and it amazes me still more that people can lose sight of that big picture so completely as to carry on the petty squabbles and power struggles that still afflict the planet.)

Discovering the true nature of the solar system was a revelation from science which turned our point of view around. Earlier we had imagined that the earth was the center of the universe, that the starry heavens and those “wanderers,” the planets, revolved around the earth. Then we discovered that the universe looks this way to us simply because this planet is the point we are looking from. We were limited to a first-planet point of view, as it were, but we had no way to realize this until we could shift our point of view elsewhere – first in imagination, by revising our concept of the cosmos, then in celestial mechanics, and later by launching ourselves (or our prosthetic viewing devices) far enough into outer space to become observers of the earth in the context of the solar system. In the 21st Century, we are beginning to see distant planetary systems in their starry context.

All scientific inquiry requires observation, but not all observation requires special technologies such as telescopes or microscopes. Amateur naturalists such as Thoreau, by looking closely at the human-scale world around them, and pondering their place in it, prepared the ground for other revelations. The idea of natural selection, for instance, was already dawning on Darwin around the time that Thoreau walked the shores of Walden Pond – but he didn't publish it until 1859 (worried perhaps about the dismay it would cause among his contemporaries).

Later on, when the molecular basis of genetic inheritance was discovered, the “missing link” in modern evolutionary theory was filled in, thus completing its broad outline. Many of the details are still under construction, and there are competing interpretations of some facts in evolutionary biology; these are signs that the theory is healthy and flourishing. Opponents of the theory, or of science generally, prefer to consider these signs of health as weaknesses, thus following in the footsteps of those who have opposed every revelation. Like the Pharisees who rejected Christ, they simply don't want their habitual view of the world turned upside down, or inside out. So they demand proof before they will “believe”; but the kind of “proof” they have in mind is contrary to the spirit and method of science. As Gregory Bateson put it (1979, 32), ‘science probes; it does not prove.’

Then there was Einstein's theory of relativity, which (much to his dismay) spawned The Bomb – meanwhile upsetting our understanding of space, time, energy and matter. All of these mindquakes have been disturbing, and continue to be so for many people. But in our time, perhaps the most astonishing of all – for those who manage to get past their dismay – is the realization that the world is inside out. This revelation is both mysterious and mundane, perfectly obvious and totally unimaginable. The explanation in this chapter may be inadequate for some readers and superfluous for others. If you are bored or bewildered by it, the author can only beg your patience, as the main thread of our story must pass through the eye of this needle.

Francis Crick, who played a role in discovering the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule, also wrote a popular book about the neuroscience of consciousness, The Astonishing Hypothesis. Here is his version of the inside-outness of the world:

In perception, what the brain learns is usually about the outside world or about other parts of the body. This is why what we see appears to be located outside us, although the neurons that do the seeing are inside the head. To many people this is a very strange idea. The ‘world’ is outside their body yet, in another sense (what they know of it), it is entirely within their head. This is also true of your body. What you know of it is not attached to your head. It is inside your head. — Crick (1994, 104)

The reason this hypothesis remains so ‘astonishing’ is that you can't see or experience the world as being inside your head, nor can you normally talk about it as if it were. The brain is in the body, the body in the world, and the part cannot contain the whole. But the whole of your feeling, thinking and knowing, your world as you see it, appears from outside you to be something going on inside you. Empirical science can only account for the fact that you experience a world by identifying the experiencing process as the work of your bodymind. Meanwhile, that world of your private experience includes how empirical science itself appears to you, because your world is outside in.

The world that exists for you is called the phenomenal world, after the Greek word phainomenon, which comes from the verb for appearing. As it often seems that you are looking out at that world ‘through a glass darkly,’ you may well decide that some appearances are more “real” than others; but nothing can be real for you if it doesn't first appear to you. This appearing has its material cause in your brain dynamics, consisting of billions of neurons firing and triggering each other in constantly shifting and looping patterns which constitute the formal cause of your experience of the phenomenal world. Its final cause is your “mission.” That is why you are the ‘sole heir’ and ‘king’ of the whole world, no matter what role your puny persona might play in the social scheme.

We cannot simply dispense with our habitual way of talking about the world, but as Crick says above, we need to speak of it ‘in another sense.’ You can do this only by projecting your point of view outside of your ‘self,’ making an imaginative leap into the role of third person, observing an iconic sign of your own brain and its maps of your body. You can do this because you can observe other bodies and learn about their brains; but you can't do it without an imaginative leap, because it is always the first person speaking, and the first person seeing. (Don't imagine that this imaginative leap is made deliberately or consciously. Ordinary human consciousness is grounded in this ‘leap,’ or in the intent which motivates it – not the other way round.)

So the revelation in a nutshell, the astonishing hypothesis, is just as our previous chapter said: the subject of your experience is none other than your living bodymind. The experiencing subject is also the subject of this book (the object of this sign) and its ideal reader. Crick's own version of this revelation/hypothesis takes a cue from Alice when she's about to wake from Wonderland. On trial in the dream kingdom, Alice loses her patience and tells the court that its proceeding is all ‘Stuff and nonsense!’

‘Off with her head!’ the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved. ‘Who cares for you?’ said Alice (she had grown to her full size by this time). ‘You're nothing but a pack of cards!’

Crick says likewise to his readers, ‘You're nothing but a pack of neurons!’ (1994, 3).

However, Crick also wrote (later in the book) that ‘the words nothing but in our hypothesis can be misleading if understood in too naïve a way’ (1994, 261). The same is true of the inside/out distinction.

What ‘inside’ and ‘in’ means is no simple question. The simple ‘in’ of a skin envelope assumes a merely positional space in which a line or plane divides into an ‘outside’ and an ‘in.’ But the ground pressure is exerted not just on the sole of the foot but all the way up into the leg and the body. From almost any single bone of some animal, paleontologists can derive not just the rest of the body but also the kind of environment and terrain in which the animal lived. In breathing, oxygen enters the bloodstream-environment and goes all the way into the cells. The body is in the environment but the environment is also in the body, and is the body.

Any living system's “view from within” is mainly of the world without, to which it must adapt its behavior in order to keep on behaving. This world includes only those things with which the subject is equipped to interact. Estonian biologist Jakob von Uexküll introduced the term Umwelt for this world delimited by the nature of the subject. The Umwelt of each species can be visualized as a bubble of perception inhabited by individuals of that species. From the inside, the inner surface of the surrounding bubble appears to be the whole world, since anything outside the bubble is either hidden from view by its opacities or mediately represented by sensory and cognitive systems.

The perceptual bubble (the “world”) varies to some degree from species to species. An outside observer of subject-world interaction will see only those features of the subject's “environment” which belong to the observer's own Umwelt. Some of these may not be included in the subject's Umwelt, because they are irrelevant to its “view from within”; meanwhile some features of the subject's Umwelt may be quite invisible to the observer, who will therefore not understand the complexity of the process observed. Yet human observers can push the envelope of their own Umwelt with a combination of inquiry, technology and empathy, enabling us to study the psychology of other species and imagine (vaguely) what the perceptual bubble of another species might look like from the inside.

Such an observer will see an organism's behavior as enacting a relationship between the subject's Umwelt and the Innenwelt constituted by its inner dynamics of feeling, intention and cognition. As structures, Umwelt and Innenwelt are complementary, each defined by its relations with the other. The interplay between the two constitutes the organism's experience of the world, most of it seen by the subject as the world and not as itself. From this point of view ‘all experience is subjective’ (Bateson 1979, 33) – it's always somebody's experience. Biosemiotically, though, experience can also be seen from the outside as the mapping of Umwelt into Innenwelt reciprocally coupled with the projection of Innenwelt onto Umwelt, or the inner surface of the perceptual bubble reflecting the subject's way of seeing. (Chapter 9 will explore this further as the modeling relation.)

The complexity of your Umwelt is a reflection of the complexity of your own bodymind. The human Umwelt appears (to us humans!) to be qualitatively different from that of any other species because our relational capabilities extend far beyond immediate biological needs, or because modeling (sense-making, theorizing) has become for us an end in itself. This enables us to reason about entities, relations and situations other than those presenting themselves to us as percepts. We imagine unknown realities and unrealized possibilities. We know of no other animal who can theorize about itself or its own Umwelt or Innenwelt; without conscious symbolizing, a living system knows only through its modeling and not about it. Not even other social animals project their attention as far beyond sense perception as we do with our enhanced means of mediation. (In other words, no animal that we know of is as absent-minded as we are.)

The human nervous system is the most complex that we know of, and each individual human has a world differing in some details from any other. So each individual inhabits a personal bubble made up of his perceptual and cognitive habits. This habitual view of the world is like a reflection from the inside surface of that personal bubble. But this person is also an incarnation of the human kind, and all humanity has its Umwelt in common: the personal cognitive bubble is nested within the Umwelt of the species. This conjunction of unity and difference makes culture and communication possible among humans. It also makes the human Umwelt so distinctively variable that some prefer to use another word for it. Husserl called it Lebenswelt (‘life-world’; Deely 2001, 10).

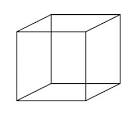

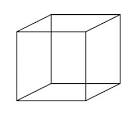

Inhabiting a lifeworld allows us to be virtual observers of ourselves, and thus to see ourselves as it were from within and without, though not quite both at once. We cannot sustain both views at the same time, just as we can sustain only one view at a time of a Necker cube:

When you see this as a transparent 3-dimensional object, do you see it from slightly above or slightly below? If your brain works in the usual way, you see it one way or the other. The front and back ‘faces’ appear to change places as you stare at it, your view flipping from one perspective to the other. Each view is a complete form or Gestalt (a term lifted from German by psychologists), and the flip is a ‘gestalt switch.’ Likewise, when you flip the first-person view of your world from outward- to inward-looking, or vice versa, the world turns inside out.

When you see this as a transparent 3-dimensional object, do you see it from slightly above or slightly below? If your brain works in the usual way, you see it one way or the other. The front and back ‘faces’ appear to change places as you stare at it, your view flipping from one perspective to the other. Each view is a complete form or Gestalt (a term lifted from German by psychologists), and the flip is a ‘gestalt switch.’ Likewise, when you flip the first-person view of your world from outward- to inward-looking, or vice versa, the world turns inside out.

We generally become self-conscious only when our interaction with the world has already been interrupted. In the normal ongoing practiception cycle (to be explored in Chapter 9), you are minimally conscious of your body (that is, of the body seen by others as you). The player immersed in the flow of the game, for instance, does not perceive her body as an object.

The tennis player learns how to be guided by perception so that the approaching ball is transferred to a designated position in the opposite court. Indeed, there is evidence that motor-perceptual learning that concerns distal events of this kind is more primitive than motor-perceptual learning that concerns merely motions of the organism's own body.— Ruth Millikan (2004, 199-200)

The enactive subject of experience is the actual bodymind, not the contents of the skin-bag seen by somebody else. So how can this enactive being view itself from within?

In Chapter 2, when you were asked to turn your attention to a mirror, you had to make a choice: either do that “literally” (and stop reading!) or imagine the experience. If you did actually look into a mirror, you must have stopped doing that in order to read on. As you read on through the words about looking into the mirror, your imagined (or remembered) experience of doing that was the object of those word-signs. When you imagine, remember or think about an experience, it becomes an object of some sign – some thought, word, image or idea. The result of that semiosic process is a new experience, differing in some respects from the more direct experience of the object, the one you are now thinking about. That new experience is the immediate interpretant of those thought-signs.

Taken as a whole, your Innenwelt is a semiotic system, a complex sign having your Umwelt as its object and the conduct of your life as its interpretant.

An “experience” that you can think or talk about cannot be your present experience, just as an object that you see outside the window cannot be your experience of seeing. An “experience” of yours, when seen or imagined from the outside (whether by somebody else or by your own remembering), can only appear as a process, or a move in the game of life. What appears from the outside as a semiotic process or event appears from the inside as immediate experience – but only so long as you don't think about it, or try to describe, imagine, remember or name it: as soon as you do that, the experience is gone, and in its place is the object of a new sign, a new nexus in the flow of semiosis.

You're not just a pack of neurons, then, but a process animating everything they do. Other people, other semiosic systems, see you as a distinct individual with ‘a local habitation and a name.’ To be an object of public attention is to play a particular role in the universal drama. On this vast stage, even a starring role is a bit part, a particle. This is the self you present to others, and to yourself in your self-conscious internal dialogue. Wearing the persona is something that you as first person can do in your sleep, and indeed most of us do it quite unconsciously most of the time, personality playing itself out like a dream. Waking up is realizing that all these persons or “points of view” are expressions or transformations of life itself. In reality, the distinction between you and the universe is local and temporary. ‘If that there King was to wake, you'd go out – bang! – just like a candle!’ This little bang at the end of time is what Sufis and Buddhists call ‘extinction’ (fana, nirvana). It's waking up to a world undivided between shadow and light, subject and object, self and other.

As a social animal, you also inhabit a cultural or communal body with its own Innenwelt or Lebenswelt – although the boundaries between cultures are less definite than the boundaries between the bodyminds of their members. A cultural lifeworld can be imagined as another bubble, inside the Umwelt but beyond the personal bubble. This communal bubble is made of shared beliefs, often represented by the “sacred stories” or myths of the culture. Myths are signs, of course, and what they represent to those inside the culture may not be evident to those outside of it.

The word myth itself is used in two different ways, as explained by Tom McArthur in his two definitions of it for the Oxford Companion to the English Language:

(1) A culturally significant story or explanation of how things came to be: for example, of how a god made the world or how a hero undertook a quest. As such, myth is opposed to history, in that it is usually fabulous in content even when loosely based on historical events. … (2) A fictitious or dubious story, person or thing: That's a myth; it never happened. Stories once regarded as true (and therefore not myths) may lose their power to convince (and be demoted to the status of myth), because other stories replace them (as pagan accounts of life were replaced by Christian accounts) or they are no longer considered relevant, credible or useful. The adjectives mythic and mythical are synonymous, but mythic is often kept for the first sense of myth (‘Mythic figures like Zeus and Heracles’; ‘a story of mythic proportions’) and mythical for the second sense (‘the mythical land of El Dorado’). In classical Greece, mythos was contrasted with logos; both derive from verbs that translate as ‘speak,’ but where mythos subsumed poetry, emotion, and mythic thought, logos subsumed prose, reason and analytical thought. The present-day dichotomy between poetry, literature, and the humanities on the one hand, and reason, logic, analysis, and science on the other dates from the anti-mythic and anti-poetic stances adopted in the 5/4c BC by such philosophers as Plato.

A myth in the first sense above can represent explicitly those universal forms or archetypes implicit within the human Innenwelt. This gives it an informing power more intimately felt than factual truth. Intimacy with the real world of imagination, the world of mythic reality, is at least as essential to our guidance systems as contact with “objective” reality and knowledge of historical fact.

The difference in usage between the mythic and the mythical corresponds to a distinction (pointed out by Northrop Frye) between the imaginative and the imaginary: the former is ‘culturally significant’ while the latter is factually untrue. But the fact is that a story, or a theory, has to be imagined, has to appear as an image, before any question of its truth can arise; and some culturally significant beliefs are too deeply enbedded in our guidance systems to be empirically testable. A genuinely mythic narrative can be a turning sign because it connects more directly with the deeper levels of intent than a factual history does. By evoking an intersubjective reality, it can unite a whole culture or subculture by implying or reinforcing a shared practice or identity.

It is only when a myth is accepted as an imaginative story that it is really believed in. As a story, a myth becomes a model of human experience, and its relation to that experience becomes a confronting and present experience. — Frye 1980, 29

Telling a fictional story is lying only when you pretend that the story is a true representation of reality. Telling a fictional story isn’t lying when you avoid such pretense and acknowledge that you are trying to create a new intersubjective reality rather than represent a preexisting objective reality. — Harari 2024, 34

The historical facts about Jesus of Nazareth, sketchy as they are, cannot compare in cultural and personal significance with the gospel stories about him and the sayings attributed to him. If you try to pin down the Savior to a fixed location in history, as an individual with a fixed proper name, you crucify him again. And he evades you again, leaving behind an empty tomb while the Holy Spirit of semiosis moves on.

From the personal world to the cultural to the Umwelt, we dwell within bubbles within bubbles enclosing our beliefs, our thoughts, our sensing and sense-making. The best feature of these bubbles is their integrity. That's what allows us to see and inhabit a whole world. But the surface tension of each bubble also obscures our vision of everything outside of it. As soon as we believe, or even imagine, that there is a real world beyond the bubble, we begin to see its inner surface as an edited, scripted, domesticated version of the wild reality outside. Then we are challenged to confront that reality, just as the knights of the Round Table were challenged to undertake a Quest for the Holy Grail. To find out what is behind that curtain, we first have to find an opening in it – possibly a break in its integrity, which might seem to endanger our own integrity, our wholeness, our health. But as the stories of the Grail suggest, the Quest is for a more universal health, grounded in the wholeness of the Primal One.

We find ourselves in the cosmos, and our mythic stories about the cosmos turn out to be autobiopsychographical. As Arthur Green suggests in an essay about the Zohar, scriptures often reflect a ‘mirroring onto the cosmos’ of one's own deepest experience.

The language of Kabbalah is cosmological. Hence, as our experiences are structured by the language system within which we work, the Kabbalist envisions his inner reality as the unfolding of universal life out of the Godhead; his chief preoccupation is the cosmos, not ‘merely’ his own soul.— Green (in Fine 1995, 48-9)

The form of that cosmic space mirrors the structure of the soul as the archetype and entelechy of the human bodymind. This body is of cosmic proportions, like the primal man of Jewish myth:

According to the Aggadah, it was only after the fall that Adam's enormous size, which filled the universe, was reduced to human, though still gigantic, proportions. In this image – an earthly being of cosmic dimensions – two conceptions are discernible. In the one, Adam is the vast primordial being of cosmogonic myth; in the other, his size would seem to signify, in spatial terms, that the power of the whole universe is concentrated in him.

In this story, Adam fell from the primal state, where he was one with the universe, into the state where power was ‘concentrated in him.’ In the 21st Century we can see this fall as the mythic genesis of the Anthropocene, which is characterized by extreme concentrations of power in human hands (Heinberg 2021). ‘By regarding ourselves as superior, we can feel justified in our domination and exploitation of nature; a hierarchical form of human-centred anthropocentrism that might be better labelled as “anthroposupremacy”’ (Bendell 2023, 26-7).

A similar story of “the fall” is told in the prophetic works of Blake and in Finnegans Wake. Like them, George Santayana conflated ‘the fall’ with a continuing creation:

The universe is the true Adam, the creation the true

fall; and as we have never blamed our mythical first parent very much,

in spite of the disproportionate consequences of his sin, because we

felt that he was but human and that we, in his place, might have sinned

too, so we may easily forgive our real ancestor, whose connatural sin we

are from moment to moment committing, since it is only the necessary

rashness of venturing to be without fore-knowing the price or the fruits

of existence.— Santayana, The Life of Reason, Vol. 3, Chapter X

We forgive our real ancestor because we sense that without venturing into the Secondness of existence, we would have nothing to know and nobody to know us. We fall into fragments lost in the cosmos, but the mediator Thirdness comes to the rescue with with the mirror-vision of mutuality intimated by the Bhagavad-Gita:

They live in wisdom who see themselves in all and all in them. — Bhagavad-Gita 2.55 (Easwaran)

In short, myth, science and philosophy agree that the world really is both inside and out. The subject and object of experience are two faces of a single coin, as it were, and not really separate, any more than mind and matter are separate. Peirce, in an 1892 article in the Monist, said this about matter:

… it would be a mistake to conceive of the psychical and the physical aspects of matter as two aspects absolutely distinct. Viewing a thing from the outside, considering its relations of action and reaction with other things, it appears as matter. Viewing it from the inside, looking at its immediate character as feeling, it appears as consciousness.

The ‘immediate character’ of a ‘thing’ is its Firstness, the quality or ‘feeling’ of a phenomenon, prescinded (abstracted) from its actual existence, significance or relation to anything else. Peirce's ‘view from inside’ is that of the ‘primal positive science’ which does not distinguish object from subject, object from sign, or even inside from outside.

The word ‘feeling’ has a different meaning in a psychobiological (third-person) account of experience such as Damasio's, where feeling is the nervous system's representation of the current state of the living body. Since the nervous system is entirely within the body,

body and nervous system can interact directly and abundantly. Nothing comparable holds for the relation between the world external to our organisms and our nervous systems. An astonishing consequence of this peculiar arrangement is that feelings are not conventional perceptions of the body but rather hybrids, at home in both body and brain.— Damasio 2021, 7

Another ‘astonishing’ hypothesis!: feelings are both physical and psychical. But Peirce's ‘viewing from the inside’ does not distinguish between ‘feelings’ and ‘perceptions’ as Damasio does. He says that we have ‘direct knowledge of qualities in feeling, peripheral and visceral’ (EP2:304). In the immediacy of conscious experience, the blue of the sky is just as much a ‘feeling’ as a stomach-ache or sleepiness. The world is divided into internal and external only by the force of Secondness, the sense of Otherness. A Peircean ‘feeling’ in its Firstness has no such duality. (Whether it is ‘conscious’ in Damasio's sense of that word is a question we'll return to later.)

Peirce's article quoted above was entitled ‘Man's Glassy Essence.’ In that phrase, which was lifted from Shakespeare (Measure for Measure, II.ii.120, quoted by Peirce below), ‘glass’ means ‘mirror.’ You and i and all selves essentially mirror one another. Likewise the physical and psychical ‘aspects’ or ‘faces’ of a thing are in some sense mirror images of each other. Which side are you on? Both – or maybe neither:

Inside and outside are inseparable. The world is wholly inside and I am wholly outside myself. — Merleau-Ponty (1945, 474)

The world is ‘inside’ in its Firstness, and you are ‘outside’ in your Secondness; Thirdness as mediation, or semiosis, carries out the inside and turns the outside in:

whenever we think, we have present to the consciousness some feeling, image, conception, or other representation, which serves as a sign. But it follows from our own existence (which is proved by the occurrence of ignorance and error) that everything which is present to us is a phenomenal manifestation of ourselves. This does not prevent its being a phenomenon of something without us, just as a rainbow is at once a manifestation both of the sun and of the rain. When we think, then, we ourselves, as we are at that moment, appear as a sign.— Peirce (EP1:38)

The way the self arrays itself is the form of the entire world. — Dogen, ‘Uji’ (Tanahashi 2010, 105)

If the ‘entire world’ as First, in its ‘immediate character as feeling,’ is a whole with no parts, as Peirce says (above), why do we see it as containing innumerable parts? We recognize things as parts of the world to the extent that we are partial to them: they play some significant part in our homeostatic self-regulation, or at least in maintaining the form of our cognitive bubbles. Sensing that we are parts ourselves, in our existence as individuals, we have to prescind the Firstness from whatever we experience. Experiencing itself has evolved along with the reciprocal minding of our embodiment and embodiment of our minds.

In Damasio's (2021) account, one's visceral feelings are more primal than sense impressions, because they represent the state of one's bodymind itself rather than anything external to it. If something outside of you means something (or matters) to you, it's because its appearing affects your “gut” feelings as well as your senses (or through your senses), and that makes a difference to (informs) the way you experience it. This difference is what we call “subjectivity.” Meaning, or Thirdness, always involves that difference, or Secondness. Or looking at it from another angle, Thirdness ‘brings about a Secondness between two things’ (Peirce, EP2:269), just as evolution brings about diversity among life forms. It governs the way things affect each other, which determines the actual form of their mutual Secondness.

The immediate character or Firstness of your consciousness must be involved in whatever you feel or know now. The universes of discourse and of reality can only be wholly thus. Heraclitus put it this way:

οὐκ ἐμοῦ ἀλλὰ τοῦ λόγου ἀκούσαντας ὁμολογεῖν σοφόν ἐστιν ἓν πάντα εἶναι.

Listening not to me but to the logos, it is wise to agree that all things are one.

We might say that the universe is necessarily a whole because the wholeness of immediacy, or presence itself, precedes the “thinginess” of any parts distinguishable within it. Only what is present to the mind can be analyzed. What i am calling ‘one presence,’ Peirce called ‘the phenomenon’ at first, but later became dissatisfied with that term and created a new word for it, phaneron:

The word φανερόν is next to the simplest expression in Greek for manifest.… There can be no question that φανερός means primarily brought to light, open to public expression throughout.… I desire to have the privilege of creating an English word, phaneron, to denote whatever is throughout its entirety open to assured observation. No external object is throughout its entirety open to observation.MS 337:4-5, 7, 1904 (De Tienne 1993, 280)

That final sentence is an important clue to what Peirce means by ‘observation’ in this context: it does not mean taking a third-person view of something, for such a view requires joint attention, which requires an object external to observers. This entails that mediated judgments about or concepts of that object are always incomplete and fallible. The very perception of something as an object involves mediation.

Does this imply that only internal objects or events are entirely ‘open to observation’? When we think in terms of individual “observers,” phanerons are internal to the conscious mind of an observer. They are what we call the “contents of consciousness.” But many constituents and processes internal to the bodymind are no more ‘open to assured observation’ than external objects are, because they are not accessible to consciousness.

In subsequent writings, Peirce often used the phrases ‘before the mind’ or ‘present to the mind’ instead of ‘open to assured observation.’ Assuming that these are equivalent expressions, they define the phaneron as whatever is presently and indubitably experienced. All of these expressions appear to imply some difference, or Secondness, between the experiencing subject and the object experienced. But as Peirce explained above, this does not mean that experiencing subjects are unable to be conscious of external objects. An example might help to clarify this.

Suppose that you are presently remembering something that you saw or said a few minutes ago. That memory is a constituent of the phaneron: you can't doubt its immediate ‘presence to the mind’ because there is no time or mental space to doubt that it is really occurring to you now. What you can doubt (in the next moment) is the veracity of the memory, its real relation to what you actually said, or the reality of what you actually saw back then – it could have been a hallucination, or a perceptual misjudgment of an external object. Semiotically, the memory is a sign of the dynamic object or event remembered. The content of the memory, so to speak, is the immediate object of that sign. Its relation to the dynamic object is open to question, but its immediate presence is not.

Does this entail that an immediate or internal object (internal to the sign in the moment of its appearance) is ‘open to assured observation’? Certainly not in the sense of ‘observation’ pertaining to scientific investigation, which is always mediated and usually takes more time than working memory can handle (more on this in Chapter 7). But the phaneron includes everything we can talk about, and Peirce called the practice of describing it phaneroscopy, defined in a 1905 lecture as follows:

Phaneroscopy is the description of the phaneron; and by the phaneron I mean the collective total of all that is in any way or in any sense present to the mind, quite regardless of whether it corresponds to any real thing or not. If you ask present when, and to whose mind, I reply that I leave these questions unanswered, never having entertained a doubt that those features of the phaneron that I have found in my mind are present at all times and to all minds.— CP 1.284

This is about as far as you can get from any specialist discourse. Peirce's point is not to deny that your experience may differ from his in some respects. The ‘features’ of which he speaks here are generic, and thus belong to any and every experience. In his Minute Logic of 1902, he proposed a triad of suggestive names for these generic ‘features’ or ‘categories’:

Originality is being such as that being is, regardless of aught else.

Obsistence (suggesting obviate, object, obstinate, obstacle, insistence, resistance, etc.) is that wherein secondness differs from firstness; or, is that element which taken in connection with Originality, makes one thing such as another compels it to be.

Transuasion (suggesting translation, transaction, transfusion, transcendental, etc.) is mediation, or the modification of firstness and secondness by thirdness, taken apart from the secondness and firstness; or, is being in creating Obsistence.

CP 2.89

Later on, Peirce often referred to these as ‘elements of the phaneron’ or ‘elements of consciousness.’ But whatever we call them, we cannot doubt that some generic ‘features’ are ever-present to every conscious mind, because such a doubt would cut the common ground from under our feet. If you and i see things differently, the logos itself compels our belief that it's because we are looking at different faces of the same things, or from different angles, as it were.

If phaneroscopy is a science, as Peirce said, it is different from all other sciences. This ‘primal positive science’ is the one aiming to find those ‘generic features’ or elements of any possible appearing. We might even say that the ‘observation’ peculiar to this ‘science’ can only be practiced by the primal person as described above. But equally essential to this practice as a science is the analysis which recognizes the universal ‘categories’ or ‘kinds of elements’ to be found in phenomena as observed.

When some constituent of the phaneron is explicitly or consciously ‘present to the mind,’ we can open up the question ‘of whether it corresponds to any real thing or not.’ Here begins the path of inquiry; and just as we are (doubtless) talking about the same phaneron, we all believe in a singular reality quite beyond what anyone thinks of it. We also believe that some of our statements can be true, regardless of whether we know or believe them to be true or not. As Peirce put it, ‘Every man is fully satisfied that there is such a thing as truth, or he would not ask any question’ (EP2:240). The fact that we have embarked on an inquiry demonstrates our belief in a reality beyond whatever bubble we are trying to look through. All our statements about it ‘have one Subject in common which we call the Truth’ (EP2:173).

What is common to all who engage in genuine dialog is a triad of universes: what appears to us ‘in here’ (the phaneron) is one; reality ‘out there’ is one; and the logos mediating between them is a semiotic universe. If you actually ‘entertain a doubt’ of this universality – a real doubt, not a ‘paper doubt’ (as Peirce called it) – then lacking any logical standard or common system of reference, you can't believe that any of us knows what we are talking about. Genuine dialogue is difficult in a “post-truth” world, where everybody has his own “reality” and nobody believes anything but their favorite stories.

And that's why, listening not to me or Peirce or Heraclitus but to the logos, it is wise to agree that all things are one. Though ‘the many live as though they had a private understanding,’ the primal person has no such illusion, and neither does the logician. Thus when Peirce speaks (above) of ‘viewing a thing from the inside,’ he is not speaking of a view from inside the thing, or even from inside an individual person, for the latter indeed is ‘only a negation’:

The individual man, since his separate existence is manifested only by ignorance and error, so far as he is anything apart from his fellows, and from what he and they are to be, is only a negation. This is man,

proud man,

Most ignorant of what he's most assured,

His glassy essence.

The biophysical world has a more-than-human reality beyond the intersubjective bubble as well as the private subjective bubble. But our only knowledge of it is mediated by our biophysical bodies. The nervous system is constantly monitoring the state of the body by means of those ‘hybrid’ signs we call feelings.

When we are conscious of those feelings, they act as explicit signs or ‘images’ of the internal being we call ourselves. As signs of something other than their own qualities, they are media, even though their appearing has the ‘immediate character’ (or Firstness) which ‘appears as consciousness’ in Peirce's ‘view from within’ as described above. This is not a self-consciousness; it is the simple awareness that is implicit in all semiosis, including perception and interoception. The Firstness of things is involved in their Secondness and in their Thirdness.

The self you are conscious of, being a function of your brain, is physically located inside your body; but unlike your view of the external world (which is also a brain function), it feels like the inside of your body. And that's not all: since your brain can monitor some of its own activity, you can feel your selfhood from the inside, not just as a living body but also as a subject perceiving some object or other. This enables you to be conscious of yourself as conscious of other things.

Human bodyminds, then, practice a special kind of self-observation – but an external observer, viewing this whole process from the outside, would distinguish between the observing self (which is the whole system) and the ‘self’ observed (which is a subprocess within the system, its function being to appear as a phenomenon within the phenomenal world). It seems likely that this rare ability could only evolve in social animals. Conscious subjectivity almost certainly develops in tandem with second-person intersubjectivity: the possibility of “having” a conscious self arises with recognition of others as selves, as experiencing subjects. This is the developmental aspect of logic being ‘rooted in the social principle,’ as Peirce put it (recall Chapter 2).

Phenomenologists (other than Peirce) commonly use the term “first-person perspective” interchangeably with “the view from within.”

To the extent that phenomenology stays with experience, it is said to take a first-person approach. That is, the phenomenologist is concerned to understand perception in terms of the meaning it has for the subject.— Gallagher and Zahavi 2021, 25

This is different from the Peircean idea of Firstness, where there is no room for a distinction between subject and object, and thus no meaning, or Thirdness. The primal person speaks (if at all) not merely from a “first-person perspective,” but rather from the original face of “self”, “world” and “consciousness of the world,” which are one and not two or three.

You might still ask how a body can recognize others as other selves (and thus have a genuine social life) without first recognizing oneself as a self. Are we chasing our tails here, thinking in circles? Why not? We live in cycles, sleeping and waking day and night, anticipating and remembering, uttering and interpreting signs, with every neuron pulsing and then relaxing to make another pulse possible. Information circulates within the body just as blood does. This kind of “circulation” is built into all living systems, including bodyminds, cultures and languages. In an ecosystem, oxygen produced by green plants is consumed by animals and the carbon dioxide they produce is consumed by plants. Animal waste is food for plants that become food for animals. We live within a ‘commodius vicus of recirculation’ (Finnegans Wake, 1). What flows around that circuit is what matters, whether we call it spirit, energy or information. We breathe it in and out, inspiration and expiration.

We are not normally conscious of breathing, but in some meditative practices, paying attention to it can make a big difference to our mental and physical lives. Similarly, we are not often conscious of how we read signs (including words and thoughts), but paying attention to how semiosis itself works can make a difference to the practice of a bodymind.

Evolution as a semiotic process is continuous, but it also involves pulses, revolutions or revelations which may strike us as punctuation marks or turning points in the flow of life and meaning. In a literate culture, these may be recorded or embodied in turning symbols or stories, sometimes “canonized” as sacred texts or “scriptures.” The next chapter will delve deeper into one intriguing collection of turning signs, the Coptic Gospel of Thomas. In the meantime,

most ignorant of what we're most assured, we collide and collude with the limits of language at every turn. Every whole-body reading of the word or of the world is a flash of light-and-darkness or birth-and-death. This was already intimated in Chapter 2 with a quotation from Dogen's Genjokoan, and here it is again in an alternate translation:

When you see forms or hear sounds, fully engaging body-and-mind, you intuit dharma intimately. Unlike things and their reflections in the mirror, and unlike the moon and its reflection in the water, when one side is illumined, the other side is dark.(Tanahashi 2010, 30)

Next chapter: Revelation and Concealment →

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

When you see this as a transparent 3-dimensional object, do you see it from slightly above or slightly below? If your brain works in the usual way, you see it one way or the other. The front and back ‘faces’ appear to change places as you stare at it, your view flipping from one perspective to the other. Each view is a complete form or Gestalt (a term lifted from German by psychologists), and the flip is a ‘gestalt switch.’ Likewise, when you flip the first-person view of your world from outward- to inward-looking, or vice versa, the world turns inside out.

When you see this as a transparent 3-dimensional object, do you see it from slightly above or slightly below? If your brain works in the usual way, you see it one way or the other. The front and back ‘faces’ appear to change places as you stare at it, your view flipping from one perspective to the other. Each view is a complete form or Gestalt (a term lifted from German by psychologists), and the flip is a ‘gestalt switch.’ Likewise, when you flip the first-person view of your world from outward- to inward-looking, or vice versa, the world turns inside out.